Dread Scott //

Testing the Limits of The First Amendment

Dread Scott is an internationally-recognized artist based in Brooklyn. In February 1989, as an undergraduate student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), Scott exhibited an installation for audience participation entitled, What is the Proper Way to Display a US Flag?

The work faced protests by veterans, was censored by local government and led to a national debate over flag desecration and freedom of expression.

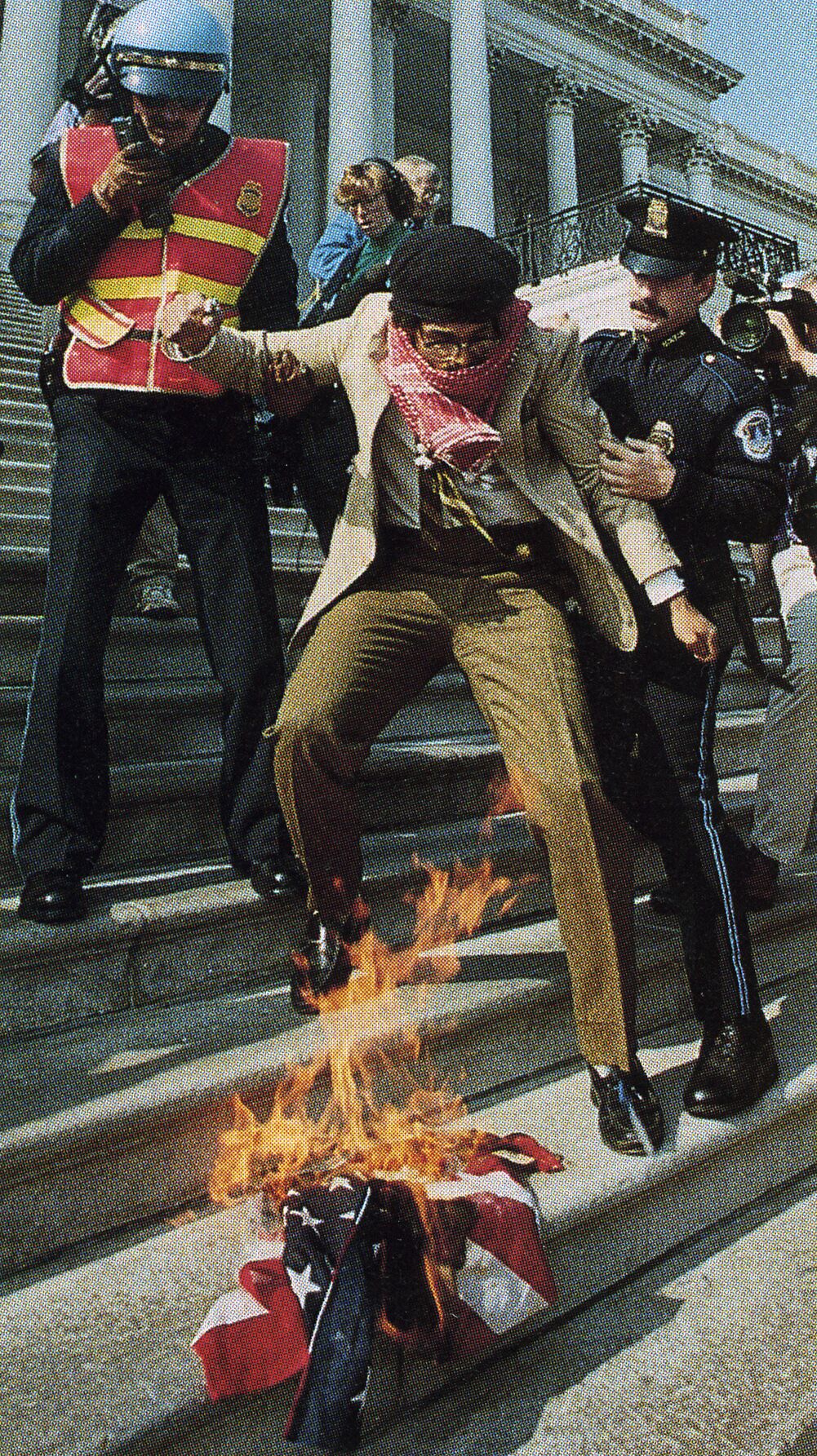

Scott was publicly denounced by the U.S. Senate, and President George H.W. Bush declared the work “disgraceful”. In July 1989, he was arrested, along with three other protestors, for burning the American Flag on the steps of the U.S. Capitol, in defiance of the Flag Protection Act of 1989. Almost a year later, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the protestors, defining flag burning as protected speech.

Our conversation focuses on various challenges to his artistic freedom and the support systems that helped him navigate those instances.

What is the Proper Way to Display a US Flag? (installation for audience participation,) 1989

Photomontage including images of flag-draped coffins and South Korean students burning US flags; a shelf with a blank book inviting visitors to write responses; and, an American flag on the floor requiring visitors to decide whether to step on the flag to submit their feedback.

Courtesy the artist Image courtesy the artist.

C: We are approaching the 30th anniversary of the controversy surrounding your work, What is the Proper Way to Display a U.S. Flag? Did censorship overshadow that work or reduce its complexity? Did it distract from any of the issues you wanted to address?

D: Yes and no. The threats of censorship were important for really expanding a conceptual artwork to a mass audience. That said, those threats shaped how people—specifically many people in the arts—see the work. Often when the work is discussed, it is in the context of being censored. A lot of artists—including at the time—really tried to discuss the work as being about free speech and that’s not what the work is about. It is actually an opportunity for all sorts of people to debate what the U.S. flag and U.S. patriotism represents, with people who perhaps feel victimized by America, having an equal footing.

One of the writings in the book, that touched me, is somebody who wrote (this was back in 1989):

This flag I’m standing on stands for everything oppressive in this system—The murder of the Indians and all the oppressed around the world, including my brother, who was shot by a pig who kicked over his body to “make sure the nigger was dead.” This pig was wearing the flag. Thank you Dread for this opportunity.

It was very much tying murder by police, police brutality, and the conditions that many black people face in this country to how they see the flag. [...]People like this, and the people who sent me death threats, often understood the work more than people in the arts community.

C: You’re providing a space for people who are critical of the flag to have that discussion, which does deal with free speech, but not in the way it was mainly represented.

D: Yeah, yeah. There were people from the housing projects, in the ghettos and barrios, art students around the country, people internationally who wrote in all these different languages in the book, of how they deeply connected to what the actual content of the work was. Allowing people from the projects to have an equal footing to discuss what the U.S. flag is—as an art critic or a Senator, or a person who wears a flag pin on their lapel—that’s uncommon and that’s why the work is particularly rich.

“I wanted to make work where the audience was implicated in the work as soon as they saw it and they could have freedom to discuss and interact with it as they saw fit. So it’s not about my view of the flag, it’s actually enabling society to have a conversation about it. The thing that became incendiary was that not everybody agreed, and transgressive views were given space to breathe.”

C: I read that veterans would roll up the flag to prevent people from stepping on it. It’s interesting in the context of intervention. Clearly they weren’t thinking of themselves as artists, intervening with your artwork, but I was wondering how you interpreted that?

D: The main participation I intended was people writing responses and potentially standing on the flag. I didn’t intend for people to roll up the flag, but that became something that was a part of it. As long as the gallery would put the flag back down so others could interact with it as I intended, that was fine. People tried to steal the flag. A state Senator brought a bucket with sand and a flagpole and stapled it to the flagpole and tried to have the gallerist arrested for damaging his staples. It was political theater, trying to utilize this artwork in a particular way, but the work encompasses all of that. People interacting with the work aren’t artists but they are part of the work.

I wanted to make work where the audience was implicated in the work as soon as they saw it and they could have freedom to discuss and interact with it as they saw fit. So it’s not about my view of the flag, it’s actually enabling society to have a conversation about it. The thing that became incendiary was that not everybody agreed, and transgressive views were given space to breathe.

C: How did School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) and organizations like the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) support or fail to support you during that time?

D: The work was in a juried student competition at SAIC. I submitted 3 works, and that was the work that was selected. Before the show opened they called me and said “hey, we changed our mind, we’d love you to switch works.” In 1989 there was not a lot of talk about censorship in the arts. At that point, the NEA 4* hadn’t happened yet, but I did know what they were asking for was wrong. I said, “Look you can censor me, but I’m not going to censor myself.” They said okay and checked to see whether [the work] was legal, and their lawyers advised them that it was.

So then a couple days after it opened—veterans showed up at the school and they assumed that people would be morally outraged that a student would dare offend them. They had a press conference in the gallery. The school started receiving bomb threats and I started receiving death threats and they closed down for a couple days—which is outrageous that a couple of vets complain and an internationally recognized art school shuts down.

I held a press conference a couple days later. I met with some faculty members to talk about how to respond to this. The faculty assumed that the administration would be on their side and support them and me—they were actually wrong—The administration was trying to contain the incident. They threatened one of the faculty members who had agreed to be at the press conference, who was a British national and a respected visiting artist. They said if you appear at this press conference we will terminate your contract and your visa will be invalid. Faculty who weren’t tenured were threatened. . . . The year prior, the school had been censored by aldermen [city council members]. A student had shown a racist, sexist, homophobic work that was removed from the walls of the school. The group show that I was part of was a response to that. The school was trying to say, we are not racist, we celebrate Black art. So they were in a really awkward position when my work became controversial. If they censored my work they would be viewed as both censors and racists again. . . The ACLU was basically good. They took a case that was a violation of a city statute and a case that was a violation of a state statute—a teacher from Virginia stepped on the flag and that ended up in court. Even though I was not technically involved in the case, they intervened on my behalf.

The ACLU sued the city on behalf of Chicago artists—including me—who did not wish to be arrested for mounting a show of flag art. They also tried to help document the death threats that I was receiving.

Dread Scott burning the American FLag on the steps of the U.S. Capitol, October 30, 1989, photograph by Charles Tasnadi, AP

While the ACLU has defended a lot of radicals and important people, they tend to look at a law as it serves their views. . . They are doing political battle through the law. There was a Texas flag burning case that had gone to the Supreme Court in 1989, called Texas v. Johnson. The Supreme Court ruled on that case in June of ‘89, that the Texas law was unconstitutional and flag burning was protected speech. Congress, in trying to overturn that decision, passed a national flag statute, [On October 28, 1989 the Flag Protection Act, made “it unlawful to maintain a U.S. flag on the floor or ground or to physically defile such flag.”] Joey Johnson, the defendant from [Texas v. Johnson], a Vietnam vet named Dave Blalock, and a revolutionary artist named Shawn Eichman and I, all burned flags on the steps of the U.S. Capitol [on October 30, 1989, in protest of the new law]. After [the national flag statute] went into law, the Supreme Court case came out of us burning [the flag] on the Capitol and the Seattle flag-burning. It’s two cases that got joined. [In June 1990 in United States v. Eichman the Supreme Court determined that burning the flag was included in constitutionally protected free speech]

When the flag burning [case] went to the Supreme Court [we were represented by] the law firm of Kunstler and Kuby and David Cole, who is now the Director of ACLU . . . Bill Kunstler was the person you go to if you’re ever in trouble with the American government. He represented the American Indian Movement, Black Panthers, Martin Luther King. He was a bad-ass people’s lawyer, incredible lawyer. So it was very different, the ACLU was trying to shape my views to their case. Bill Kunstler let his clients say what they wanted to say and used the law to defend them. The ACLU kept my ass out of jail and allowed my art to thrive but it is still a different approach.

In terms of support among the art community, artists nationally were really supportive:

Leon Golub, Richard Serra, Jon Hendricks, Coosje van Bruggen and Claes Oldenburg were incredible. Richard happened to be in Chicago at a time when one of the student demonstrations in support of the artwork was happening. He was one of the most respected sculptors in the country at that time and he came to this student demo.

C: Was this before [Richard Serra’s] Tilted Arc was taken down ?

D: I think it was after, but the battle had already started around that.

C: So he was empathetic?

D: Richard Serra is a minimalist sculptor but he is a pretty radical guy and I think his work reflects that. He is not aloof from students. His work is censored a fair amount and some of his best work isn’t in America. . . because cultural ministers in Germany will support interventions into public space, that American departments of culture won’t. The fact that his Tilted Arc gets taken down when it was commissioned by the U.S. government, it tells you something.

“Artists are money launder- ers. We take perfectly dirty money that comes from lots of bad places and if we’re good we clean it up and do something good with it.”

So yes, he was conscious about censorship in a personal way, but it’s bigger than that. And Leon Golub was a bad-ass artist. He had been fighting for oppressed people in lots of different ways and had dealt with censorship and people ignoring his work because of the content for a long time. So they wrote letters of support.

When the Texas flag burning case [Texas v. Johnson] went to the Supreme Court, there was an amicus brief* (a friend of the court brief) filed by twelve very well known artists: Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Richard Serra, Faith Ringgold, John Hendricks, Leon Golub, Nancy Spero, and a couple others. They were already thinking about free speech and the flag for a while—all have used the flag in their work.

‘A Partial Listing Of People Lynched By Police Recently’ Billboard by Dread Scott

C: You were working on a billboard project in Kansas City with the image of “A Man Was Lynched By Police Yesterday” for a Black Lives Matter exhibition. The billboard company refused to show it because of the content? . . .

D: 50/50, the place in Kansas City, had a contract with a billboard company [Outfront Media] to rent a billboard for a year. They approached me and I submitted a design. The art space loved it. They sent it to be put up and the billboard company said, “No you can’t do that. This is not factual and it’s offensive.” “This is literally just saying the names of people killed by police, what’s not factual about that?” “You can’t call that lynching.“ So the National Coalition Against Censorship wrote them and we came up with a way to redesign it. The billboard just had names of people who were killed as hashtags and we displayed the A Man Was Lynched By Police Yesterday banner next to it. It was messed up that a billboard company could censor it, but ultimately the message got out to the people.

C: I’ve been trying to understand the differences between private spaces and public spaces. If it’s a corporation, that’s their private space so it’s not really protected under the First Amendment.

D: First off, I think artists should have a better understanding, both of what censorship is and what the First Amendment is. The First Amendment is about the government restricting speech and—in a certain sense—who wants to live in a country where you can’t criticize the government and government policy? It’s specifically written to prevent federal government and state government from preventing people from demonstrating, and from publishing and making art about what they want.

The overwhelming majority of space allowed by government action to exist in the public sphere are billboards and they are controlled by five media companies. Having corporate messages pumped out to people: buy a car, buy soap, buy, cigarettes, whatever. That’s perfectly okay. When people complain about what the billboards show, they rely on their right to do this and part of their argument is the First Amendment, even though it’s not a legal right, but it’s our precedent.

When they wish to censor something they say no, no, no, we are a private company. We can show whatever the hell we want. In trying to show ‘A Partial Listing Of People Lynched By Police Recently’ (in Kansas City), but also the For Freedoms billboard, the billboard companies are saying, no it’s our space, we can rent it to whoever we want, for whatever we want and we don’t wish this message there. . . They can have police murder unarmed people—it’s an epidemic. In [2016], the year that [‘A Partial Listing Of People Lynched By Police Recently’] went up, they killed 1100 people. Why can’t we just factually recount some of the people that were killed? What’s wrong with that message?

“Legally I have defended my work on the basis of the First Amendment, but I am an advocate for censorship. I think all societies censor. I do not believe in the unrestrained dissemination of all ideas.”

C: Since you brought up corporate spaces and funding I’m curious if you are selective about where your funding comes from or who you sell to.

D: Artists are money launderers. We take perfectly dirty money that comes from lots of bad places and if we’re good we clean it up and do something good with it. . . There are many institutions and individuals who I sell to who don’t necessarily share my values—in some cases, who my work is critical of—but from a money laundry perspective, I am able to take that and engage in conversations broadly throughout society.

C: In England there is a student movement to differentiate between censorship and not giving a platform. It’s called the no-platform movement. Used in the case of the holocaust-deniers, for example. What are your thoughts on that approach?

D: I was recently at a conference and there was a comparatively young student in his 20s, black student at an elite institution, who wanted to invite people like Charles Murray onto campus. [Murray is] the author of the Bell Curve, and a eugenicist who has anti-scientific theories that rationalize racism and white supremacy. This black student was saying, we really need to hear these controversial ideas. And I’m like, no, those controversial ideas cause a tremendous amount of harm. It is not helpful to have completely discredited, unscientific ideas, that actually are popular among some people–particularly racists–to give them a platform to dominate much of society.

Legally I have defended my work on the basis of the First Amendment, but I am an advocate for censorship. I think all societies censor. I do not believe in the unrestrained dissemination of all ideas.

I think people who want a future without oppression need to not be so enamored with the illusion of free speech that is promoted in the United States—the illusion of democracy as the pinnacle of existence—without discussing which class that democracy serves, without actually thinking about the real and actual history of America.